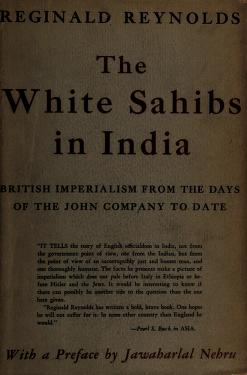

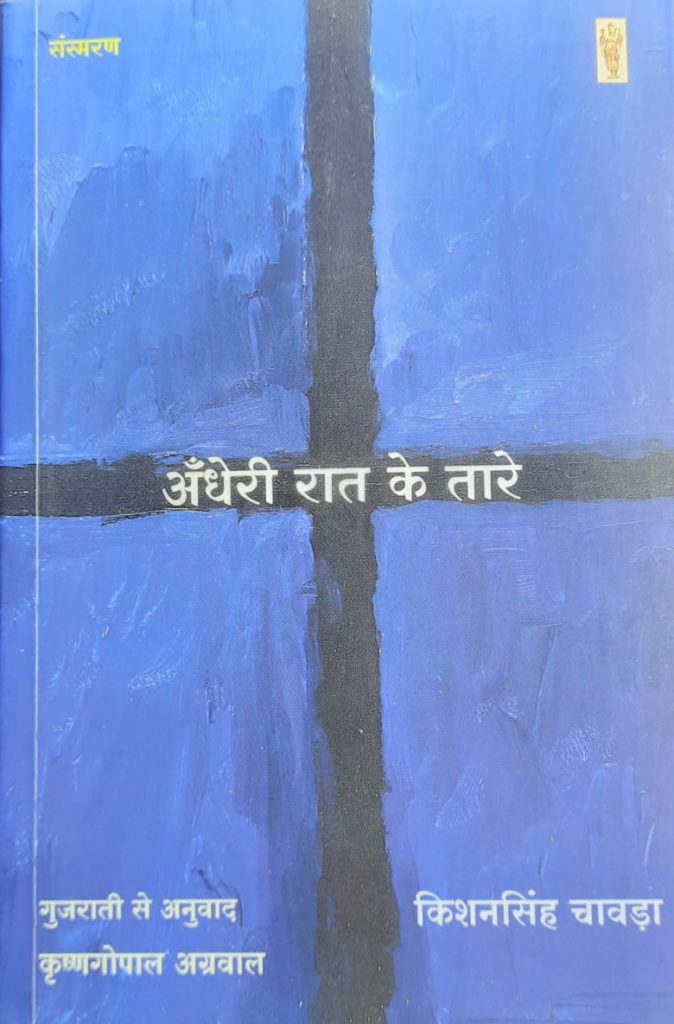

SIDH wants to bring out books written in our languages that helps us to see India, it’s samaaj, it’s ways, it’s aesthetics from our indigenous perspective. ‘Andheri Raat Ke Taare’, which was out of print for a long time, is the first book in this series. We are extremely happy that this classic has now got published. The following is the introduction that Pawanji wrote for this new edition…

ख़ुशक़िस्मत हूँ मैं। कृपा है कहीं से कि जीवन में अद्भुत और जिनके प्रति स्वतः श्रद्धा पैदा हो, ऐसे लोगों से बग़ैर ज़्यादा कोशिश किये, मिलना हुआ, और इतना ही नहीं, उनसे घरेलू सम्बन्ध बने। इनमें से एक धरमपाल जी थे और उनके मार्फ़त “गुरुजी” रवीन्द्र शर्मा के बारे में पता चला। पहली ही मुलाक़ात में आत्मीयता हो गयी। “गुरुजी’ शुद्ध मौखिक परम्परा के व्यक्ति थे। क़िस्से, कहानियाँ, अपने अनुभव में आयी बातें। उन्होंने जो देखा, सुना उसे सुनाते और उनके तार एक-दूसरे से जोड़ते जाते थे। ऐसा अहसास देते थे कि वे पढ़ते-लिखते नहीं ही होंगे। पर ऐसा नहीं था। कभी-कभार उनके मुँह से कुछ किताबों के नाम निकल पड़ते थे।

उन्हीं से सबसे पहले किशन सिंह जी चावड़ा की इस अद्भुत किताब, “अँधेरी रात के तारे” के बारे में सुना। कहीं मिली नहीं, लोगों से, जानकारों, जो लोग पढ़ने-पढ़ाने वाली जमात के थे अपनी मित्र मण्डली में, उनसे पूछा। किसी को पता नहीं। किसी ने नाम तक नहीं सुना था। फिर कहीं से एक फ़ोटो प्रति मिली। बहुत साफ़ भी नहीं थी। थोड़ा पढ़ा तो मज़ा आ गया। पहली बार किसी किताब को पढ़ते वक़्त ऐसा लगा कि, ‘भई धीरे-धीरे पढ़ो, कहीं जल्दी ख़त्म हो गयी तो?’ जैसे किसी स्वादिष्ट पकवान को सबसे बाद में खाते हैं, बचा कर रखते हैं कि स्वाद लम्बा चले, कुछ-कुछ वैसा। चाय को चुस्की लेकर पीते हैं, जल्दी नहीं, वैसा।

“गुरुजी” रवीन्द्र शर्मा जो बातें करते थे उनसे मेल खाते क़िस्से, इसमें भरे पड़े हैं। वाह। ऐसा अद्भुत और रंगीनियों से भरा, वैविध्य लिए हुए देश कभी हाल तक था-यह हमारा भारत। मज़ा आ गया सोचकर, कल्पना करके ही। और इन्होंने, किशन सिंह जी चावड़ा ने तो जीता जागता देखा है इसे। महात्मा गाँधी से लेकर, अद्भुत गाने वालियों के क़िस्से। उनकी गरिमा और हिन्दू और मुसलमान बाईजीइयों में बारीक भेद। फ़कीरों से लेकर राजाओं और महाराजाओं के क़िस्से। एक आम मन्दिर में साधारण लोगों की गाने की महफ़िल से लेकर फ़ैयाज़ ख़ॉन साहब के गायकी की बारीकियों। श्री अरविन्द से लेकर गुरुजी रवीन्द्रनाथ के क़िस्से। क्या छोड़ा? हर वर्ग, हर सौन्दर्य, हर रस को समेटे हुए अपनी सहज, साधारण भाषा में, एकदम खरे क़िस्से और इनकी पैनी दृष्टि। क्या कहने? हमलोग “गुरुजी” की पैनी दृष्टि की दाद देते थकते नहीं थे। वे वो देख लेते हैं और दिखा भी देते हैं जो हम मूढ़ों को सामने होते हुए भी नहीं दिखता। किशन सिंह जी की दृष्टि, उनकी लेखनी वैसी ही मिली।

ऐसा लगा इस किताब को तो लोगों के सामने लाना ही चाहिए। बहुत ज़रूरी है। हमारा पढ़ा-लिखा वर्ग जो आमतौर पर अपने देश के बारे में भी दूसरे देश के लोगों, या उनके पढ़ाये भारतीयों से समझता है उसे यह एक सच्चा खालिस नज़रिया भी देखने-पढ़ने को मिले तो सही, भले ही वह इन्हें काल्पनिक मानेगा। पता नहीं। सोमय्या प्रकाशन को सम्पर्क किया जिन्होंने इस किताब के हिन्दी अनुवाद को छापा था। वे अपना प्रकाशन बन्द करने का निर्णय ले चुके थे। उन्होंने ढूँढ़-ढाँढ़ कर बची हुई ५ प्रतियां मुझे भिजवायीं और कहा “आप जो करना चाहते हैं, कर सकते हैं।”

इसी के कुछ समय पहले कमलेश जी को ४ घण्टे बैठाकर “गुरुजी” रवीन्द्र शर्मा को सुनाया था। वे तो लट्टू हो गये “गुरुजी” पर। कहने लगे, “पवन जी, मेरे जीवन के सबसे अनमोल ४ घण्टे आपने मुझे दिये”। अपने भारी भरकम बीमार शरीर को वे गुरुजी के पास आदिलाबाद ले जाने को लालायित रहते। हम सब डरते रहते। गुरुजी भी। उसी समय मुझे यह “अँधेरी रात…” मिलीं। कमलेश जी को दिखायी और अपने मन की बात कि इसे दुबारा छपवाना चाहिए, बतायी। वे तुरन्त राजी हो गये। “अँधेरी रात के तारे” तो मूलतः गुजराती में लिखी गयी थी, हिन्दी में अनुवाद हुआ था। कमलेश जी को लगा कि इसे थोड़ा सा सम्पादन की ज़रूरत है। वे करने भी लग गये पर इसी बीच चल बसे। फिर उदयन वाजपेयी जी से बात हुई और उन्होंने इसे छपवाने का जिम्मा लेकर कृपा की।

“अँधेरी रात के तारे” दुबारा छप कर लोगों के पास पहुँचेगी यह सोचकर भी रोमांच हो रहा है। किताब है ही इतनी अद्भुत, आज तक फोटो प्रतियाँ करवा करवा कर अपने मित्रगणों में जो रसिक हैं उन्हें भेजता रहा हूँ। अब एक सुन्दर रूप में भेज सकूँगा, इसकी बेहद ख़ुशी है। इस तरह का साहित्य हिन्दी एवं अन्य भारतीय भाषाओं में बिखरा पड़ा है। हमारे देश का दुर्भाग्य ही कहा जा सकता है कि हमें इसकी वकत नहीं। पर कोशिश तो करनी पड़ेगी कि इस प्रकार का साहित्य आमलोगों तक बहुंचे और वे जिसे महात्मा गाँधी “भारत की आत्मा” कहते थे, इसके दर्शन कर पायें।

‘Andheri Raat Ke Taare’ is published by Vagdevi Prakashan and is priced at Rs 450. If you are interested in buying copies, we can provide the book at the following discounted price:

1-4 copies: Rs. 400 plus postage

5-10 copies: Rs. 360 plus postage

11+ copies: Rs. 315 plus postage

Please write to sidhsampark@gmail.com to take the conversation forward. Namaste!