(The following is the script of the audio-visual component of chapter 8 of the SIDH online course – ‘Understanding Modern Education -An Indic Perspective’)

Our experience of reality has two aspects: The stable, unchanging, intrinsic, unseen, intangible, BEING part. We are calling it the STHITI. And the changing, sensorial, tangible, manifested, DOING or behaving part. We are calling it the GATI. STHITI and GATI are like two sides of the same coin.

We have already talked about some sthiti/ gati pairs in previous chapters. Let us first look at the ‘I’ and ‘We’ identities. The ‘I’ identity is gati-centric. It is mostly about quantitative aspects like wealth, status, income, degree, clothes, material possessions etc. All these can be compared. In contrast, the ‘We’ identity is sthiti-centric. It is mostly about qualitative aspects like honesty, integrity, courage, and pride in one’s culture and traditions etc. For example, it is possible to hear someone say that ‘No one steals in our samaaj’ or that ‘we are brave people’.

We have also earlier looked at word and meaning. You can now easily see that word is the gati aspect and the meaning is the sthiti aspect. Words are external symbols that are IN a language, whereas meaning is always an inner process that is BEYOND language. Knowing the word and not the meaning is no good but knowing the meaning and not the exact word may still serve our purpose. The word is a symbol which is different in different languages whereas meaning is existential.

Let us look at some other Gati/ Sthiti pairs to make the distinction clear.

We can start with hearing/ listening that is directly connected to word and meaning. We hear a word but we listen to the meaning. So hearing is the gati aspect and listening, that is to do with understanding the meaning, is the inner, sthiti aspect.

Another important distinction between Information and knowledge is being ignored in present day education. Information is something that keeps changing both with time and space. It doesn’t remain the same. Information needs to be remembered or stored to be retrieved later. Knowledge on the other hand is something which once gained becomes ones own and does not need to be memorised. Strangely, any book of general knowledge today is only full of information. This adds to the confusion and information is unknowingly ASSUMED to be knowledge.

Finally let us look at the distinction between getting influenced and getting inspired. Influencing or impressing is always with the outer veneer, the gati, whereas inspiration is always an inner process, to do with sthiti. Getting influenced leads to imitation and comparison. On the other hand we get inspired by the intrinsic, qualitative aspects which cannot be copied. The quality gets manifested in different individuals naturally and in their unique manner.

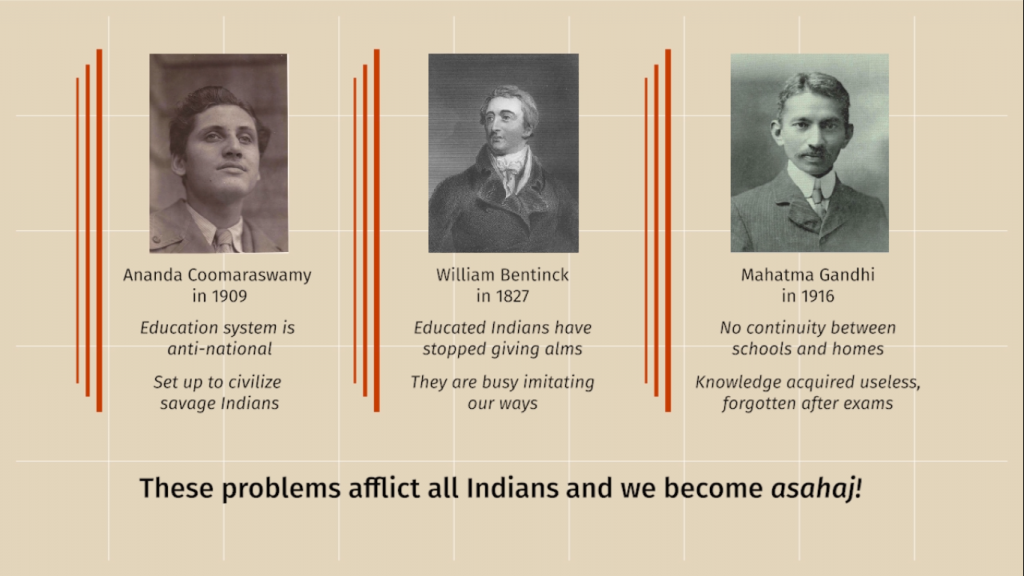

Modern education and modern systems are almost entirely gati-focused. If you are only focused on gati, you are prone to be manipulated. Because gati, like fashion, keeps changing and the people in control of setting these trends are faceless. Once these parameters are accepted almost unconsciously by us, we end up constantly comparing ourselves with the other, leading to irresolvable tensions. Education needs to be sthiti focused and gati needs to be treated the way it is, subordinate to sthiti. The decision-making if it is sthiti-centric, then the doing, the manifested, gati part would naturally follow taking into account the circumstances. In the process of education, the shift of focus from gati to sthiti will help create grounded children with Nirapekshsa Atma-Vishwas and authentic, sahaj behavior.

The above can be summarised in a table as shown below:

| Gati | Sthiti |

| ‘I’ IDENTITY (Wealth, status, income, degree, clothes etc.) | ‘WE’ IDENTITY (Honesty, integrity, courage, pride etc.) |

| WORD (Hearing) IN language/ symbol | MEANING (Listening) Beyond language/ existential |

| INFORMATION ASSUMED to be knowledge | KNOWLEDGE No need to memorise |

| INFLUENCING/ IMPRESSING Leads to imitation | INSPIRATION Cannot be copied |

(Notes:

– The other posts on this blog about the SIDH online course are here, here and here.

– The course is available here.)