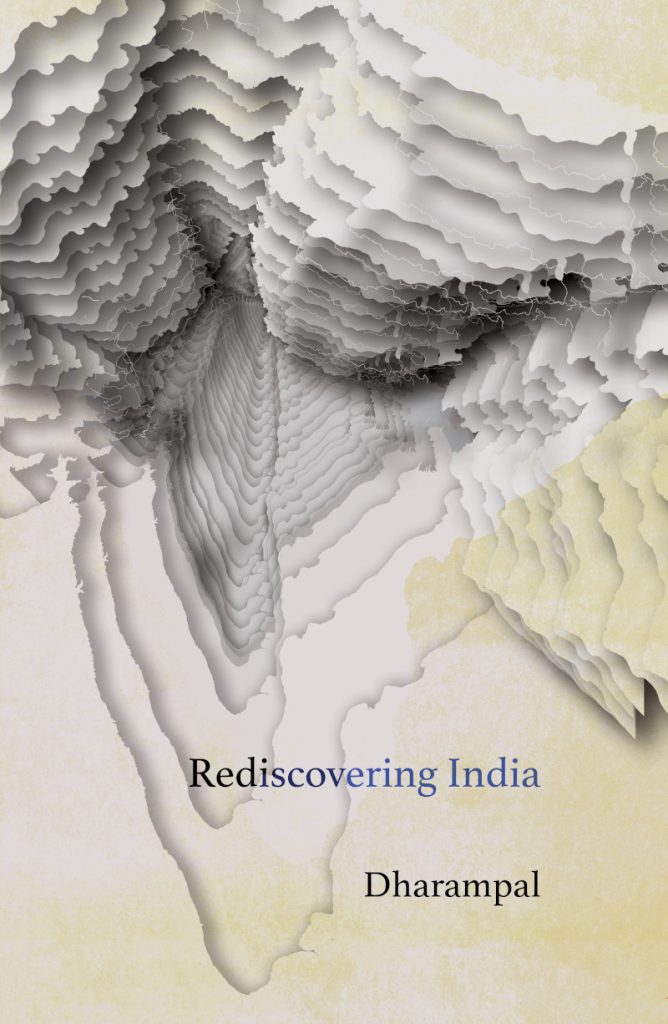

At SIDH we are republishing an out-of-print book, ‘Rediscovering India’, by Dharampalji. With a foreword by Chandra Shekharji, former Prime Minister of India, it is a book of essays and speeches (1956-1998) in which Dharampalji talks about a wide range of topics. The book has 27 chapters divided among three main sections:

- Indian Society at the Beginning of European Dominance and the Process of Impoverishment.

- Problems Faced by India after the End of European Dominance.

- Some European Characteristics and Their Worldwide Manifestations.

The following are some excerpts from the book:

“Over the last 40 years, Dharampal has written several articles, given many talks, read papers in conferences and seminars. These are significantly different from his research work, where he has by and large refrained from interpretations. These articles are based on the insights gained by him during the painstaking research and from his dwelling on them later on. In these articles, Dharampal is speculative, tries to conjure a picture of what the Indian society may have been like, how it may have functioned, taken its decisions, arranged its affairs, what were its ways of protest etc. before or immediately after the arrival of the British. It also tries to draw a picture of the manner in which the British may have looked at our (alien) ways and how the systems imposed by them must have contributed to disrupting the society. Perhaps for the first time the articles have been collected and put together for readers to get a glimpse into Dharampal’s world.”

– From the Preface to the first edition written by Pawan Gupta in 2003.

“I think it is a false impression that the early nineteenth century British mind was in any sense concerned with economic or social backwardness of India and that its usage of terms like ‘ignorance’, ‘misery’, pertain to any socio-economic context. What obtained in the early nineteenth century Britain were a well-defined hierarchical structure, a rigorous legal system, an administrative and military structure admission to which was based on birth, patronage or purchase. To such a mind the liveliness of ordinary Indian society, its relative cohesive social structure, its educational institutions, admission to which did not depend on wealth, its joint ownership of land, etc. were points not in its favour but elements which indicated its depravity and laxity.

There was a debate in the House of Commons in 1813. Many members were of the view that the people of India and the Indian society (in spite of the turmoil and disorganisation it was passing through) were still to be envied for their enlightened manners, their tolerance, their social cohesiveness and their relative prosperity. The debate was primarily concerned with the saving of the soul of the Indian people and its main mover was the great nineteenth century Englishman, Mr. William Wilberforce. He argued that Greece and Rome were wretched till they got converted to Christianity. Therefore, it was impossible that the Indians could be happy, enlightened, in their unchristian state. Mr. Wilberforce concluded that India must be wretched, depraved and sunk deep in ignorance till they could become Christians.”

– From the chapter titled ‘India must rediscover itself’.

“Having taken it for granted, on the basis of what the West popularized about itself, that the history of European man and his aspirations and theorizations had some universal validity, we also seem to have assumed that we were also capable of repeating what the West had done in the past 1,000 years of its history. The images we had of Western man were either of the individual plunderer of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, or the Western man of the twentieth century – sophisticated, polished, considerate, charitable, and at least theoretically, advocating equality and fraternity amongst all men. . . . We did not realize that to reach this present dazzling stage the West had to be harsh, cruel, exploitative, etc., not only to the non-Western world but to its own people for many centuries. The supposition that the West has arrived at its present democratic and welfare arrangements because these had been in-built in its medieval and early modern society is as much a myth as the supposition that the people of India led impoverished and politically oppressed lives for thousands of years.”

– From the chapter titled ‘The question of India’s development’