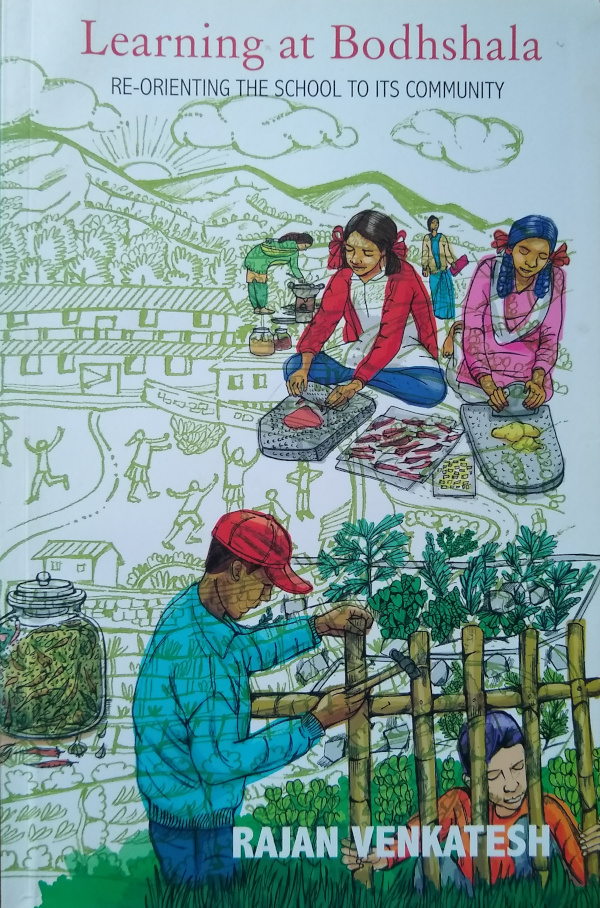

This week we look at some excerpts from a SIDH publication, Learning at Bodhshala, that chronicles a unique educational experiment. I think that, in times to come, this book may become required reading for anyone trying to re-imagine a truly Indian education.

Excerpt 1: (The eye of commonality, page 1)

I soon realised that, with children, it is not difficult to introduce farming or any useful productive work in the classroom. However, when a child goes through a mainstream school, he emerges 12 or 15 years later as a young adult, who will resist any out-of-the-textbook, real-life learning. This is indeed something amazing about modern schooling – it makes us uniformly useless in a productive environment. Urban society has accomplished this efficiently and the same model is being thrust on rural schools.

Excerpt 2: (The eye of commonality, page 29)

Our reading of Gandhiji and his vision of buniyadi shiksha, i.e., basic education, also provided direction. Soon our farm produce activity grew into a full fledged Production-Integrated Basic Education programme. It ran for three years, during which the learning activities at Bodhshala school resulted in the production of recycled hand-made paper, value-added food items, ayurvedic medicines, soaps and creams, cloth bags, paper bags and envelopes, and learning material such as number rods and the abacus.

Excerpt 3: (Food and health, page 34)

Mandua began to be regularly cooked in our kitchen, and so was jhingora as and when it was available. This had an unexpected effect on both parents and children. Visitors from the community would be pleasantly surprised and were prone to say, ‘oh, so you eat mandua too!’ This went a long way in bridging the gap between home and school.

Our teachers, too, rediscovered the joys of traditional Garhwali cooking, which they remembered from their childhood. Some of them were eating this at home, but joylessly, because schooling and the modern systems made the millets appear inferior. I then realised how detrimental schooling is to health.

Excerpt 4: (Production-integrated basic education, page 83)

The cruelty is now global; governance and science are both subservient to business, there is no ethics. The minimum and adequate response is to take farming back into our own hands. Every family must grow some of its food, not only the village family, which must be encouraged and supported to continue doing so, but the urban family as well, who must be educated about the significance of regaining this lost independence.

In that sense, I believe that natural farming or rishi kheti is the modern-day charkha. I also feel that Gandhiji, if he were here today, would approve of this; he would wholeheartedly encourage the self-production of food in a sustainable way.

Excerpt 5: (Production-integrated basic education, page 93)

The paper industry, in particular, is a double villain because apart from creating pollution at the output end of the process, it is also destroying forests at the input end. Our students were shocked to learn all this, and said that these polluting industries ought to be shut down. ‘What will we do for paper?’ asked a teacher. ‘We will find a way,’ they replied, with the new-found confidence from having made their own paper and notebook. It would be tempting to dismiss this as innocent bravado, but the important point is that these children were willing to face a truth which adult society has been evading.

(The list of SIDH publications is available here. If you want copies of ‘Learning at Bodhshala’ or any other publication, please use the contact form on the SIDH site to place your order. If you face any problems, please write to me at arun@aslishiksha.com)

One reply on “Learning at Bodhshala”

We have come far away from life. Still there is hope we can get back to life. Let us all help one another in our own ways and capacities.