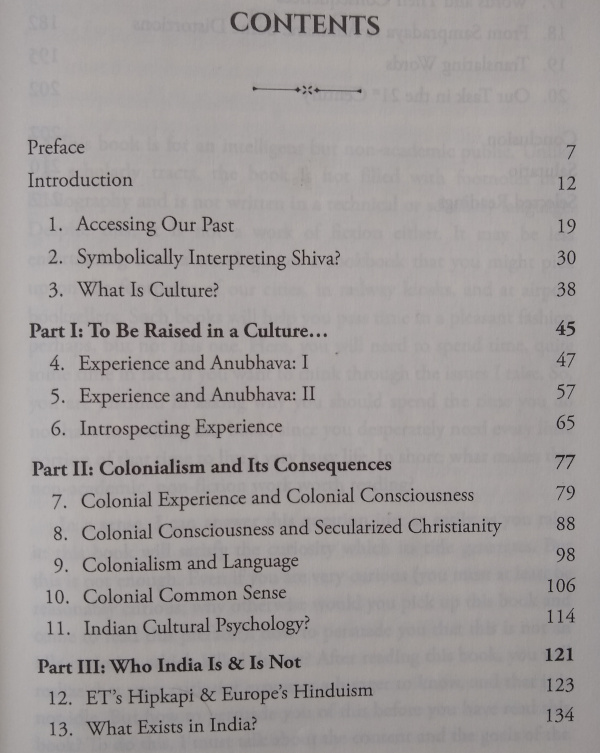

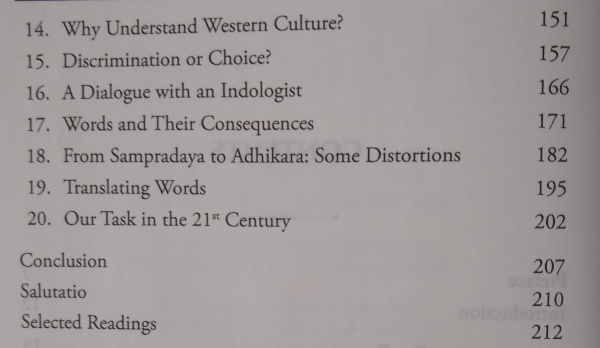

A new book by S.N. Balagangadhara, Balu to his many admirers, has been published recently. Prof Balu is an original thinker and this new book presents his ideas in a manner accessible to a lay audience. Every time I listen to a video or read something written by him, I come away with important new perspectives that clarify my understanding. Given below are some excerpts that may get you interested in buying and reading the book. I highly recommend that you do!

Excerpt 1:

I think our culture is going to see a renaissance. Such a renaissance is of importance not just to us, Indians, but also to all of humankind. Because this is going to lay the real foundation for the sciences of the social, it will provide a surprising answer to the question, ‘what does it mean to be ‘Indian’?’ This process is going to take place – sooner, if we accelerate the pace; later, if we do nothing about it. In the latter case, this may not happen in your lifetime or mine; but happen it shall. Of this, I am utterly convinced. It is this conviction that has kept me going all these years; it is the same conviction that has made me want to reach out to you.

Excerpt 2:

Any group that survives as a culture would thus have built two extremely rich storehouses containing two things: linguistic items and actionable items. Even though this distinction appears simple, their diversity and complexity are enormous: human languages and human institutions are extraordinarily varied. The latter – whether family, marriage, rituals, child rearing, schools, clubs, legal and political organizations-are congealed human actions. Poems, stories, theories, hypotheses, speeches, and talks are embodied in languages. As we grow up, our elders draw upon these multiple storehouses to educate us. Through education, we learn to make our environments habitable, i.e., learning is a way of creating a habitat. As we learn, we also draw upon the treasure chests that our teachers use.

Not only do we draw upon these resources, but we also learn how to use them both to learn and to go about with things in our two environments. The same consideration applies to those who teach us. They too use this reservoir of knowledge to teach us to use it better. Because these resources used by both teachers and their pupils help us to relate to others, we could call them the ‘resources of socialization’.

In simple terms: human beings are socialized using the resources of socialization. As I indicated earlier, in this process, we also learn how to use these different resources. In the broadest terms, this is what a ‘culture’ is: the available resources for socialization and their uses.

Excerpt 3:

I suggested above that religion produces and reproduces a configuration. In that case, how do we understand the role of Christianity and Islam in India? Are not the followers of these religions socialized differently because of their religion, and is not their presence a disturbing factor for Indian culture? Why would these religions not produce their configurations of learning and adapt instead to the Indian configuration of learning? My answer will be simplified here again: when these religions entered India, they met a culture that was already formed as a stable configuration of learning. As a result, these religions had to adapt themselves to this culture to survive. That is, these religions could continue to hold their beliefs and practice their religious activities only by adapting to Indian uses of the resources of socialization. Thus, Indian Christianity and Indian Islam remain Indian irrespective of their religious beliefs and practices. The specificities of their religions are given a space to survive and flourish in Indian culture as one of the many diversities present within it. In this process, these religions themselves undergo modifications and changes in how the believers live their daily life, which does not affect their beliefs (say about Christ or Mohammed) or their places of worship. It is this kind of adoption of and adaptation into Indian culture that many Madrassa schools fight. It is this adaptation to India that Catholicism and Protestantism in India have undergone which the Evangelical Christians militate against. Whether such resistance has any effect at all or not depends not on their militancy but on the vibrancy of Indian culture. A vibrant Indian culture (because it is a culture) allows a place for these religions and absorbs their drive to create other configurations of learning within its own multiplicities that constitute a configuration of learning. These religions, on their own, cannot do what the military, economic and administrative powers that supported them, viz., colonialism, could not do, which is to destroy Indian culture. However, this does not mean that the two colonialisms did not damage Indian culture. They did, and their effects are still visible. We will discover what these are in later chapters.

Excerpt 4:

Reflection on experience is sensible only in relation to non-introspective thinking. Introspection does not make experience accessible; instead, it takes us away from experience. It creates a self-sustaining loop by sending us to a place where experience is impossible but results only in an endless series of imaginary thoughts. When we think, all we do is blame ourselves: recrimination, beating ourselves up endlessly, feeling guilty, etc.

The first step in thinking about experience the Indian way, as I see it, is to break free from introspection and desist from reflecting on thoughts and feelings, etc., as being unique and individual. Then we can come to an understanding of ourselves and our psychologies by discovering how human we are. To understand why human beings react in specific ways is to understand them; we must see our own reactions and responses as ‘facts’ of a hypothesis. This is also an activity: we actively learn how to deal with our idiosyncrasies. Growing up as an Indian is to learn these things and to transmit them as well.